| t is the afternoon of 27 June 1876, on the Little Bighorn River in southeastern Montana. Members of the besieged group of soldiers from the Reno Hill entrenchment sadly explore the scene of "sickening, ghastly horror" on Custer Hill. They now know the answer to the question that so many had repeatedly asked two days before..."Where's Custer?"

As they walked among the bloating, decaying bodies of their fallen comrades, all was still. As the cavalrymen bowed their heads in silent prayer before beginning the odious task of burying the dead, the silence was abruptly broken by the faint whinny of a horse. As the men looked up and searched the broken terrain with weary, tearful eyes, down by the river a horse was struggling to get to its feet. Several of the men recognized the horse because of its peculiar buckskin-like color. It was Comanche, the favorite mount of Capt. Myles Keogh, who had valiantly rallied the men of "I" Company right up to the end, when they were overwhelmed by the charge of warriors under Crazy Horse and Gall. The horse was on its haunches, seemingly too weak to move any further. He had apparently sustained at least seven wounds, and his coat was matted with dried blood and soil. CPT Nowlan ordered the men to get water for the horse from the river. Several other troopers coaxed the horse onto its feet and led it away. The farrier field dressed the wounds. Comanche marched with the command to the junction of the Little Bighorn and Bighorn Rivers, and was loaded aboard the steamer "Far West" with the battle casualties, heading home to Fort Lincoln. Comanche never again was to charge to the sound of the bugle. For the next 15 years he served as the spirit of the Seventh Cavalry supporting them throughout the remainder of the Indian Wars. Symbolically, he died in 1891, soon after The Wounded Knee Conflict, established to be the end of major hostilities between the Native Americans and the military. TAPS, for an old soldier who served his country well, in so many ways.

|

|

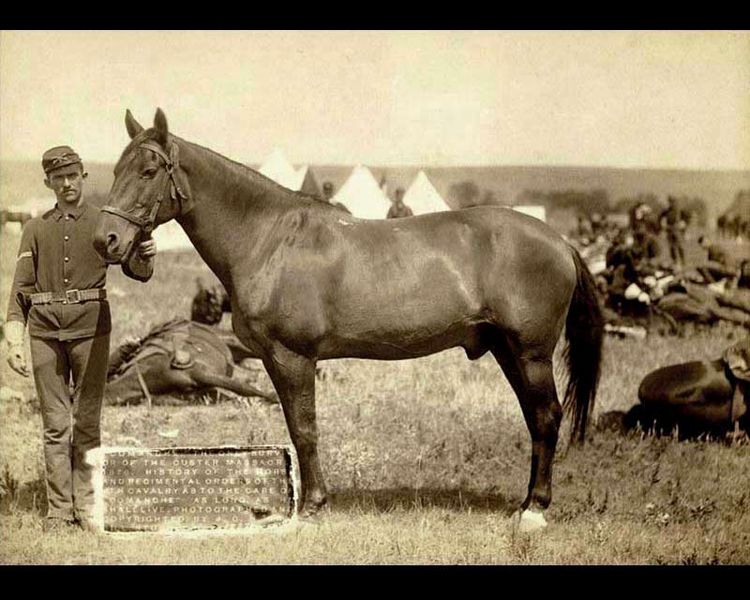

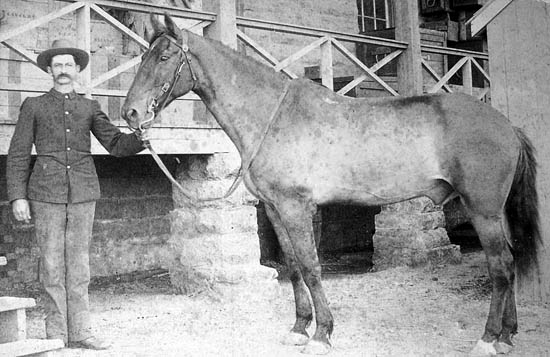

A fully recovered Comanche at Fort Lincoln after the Battle

|

| Comanche is now remembered as the only surviving member of LTC George A. Custer's immediate command at the Battle of the Little Bighorn. He has always been a symbol of the role of the U.S. Cavalry in the taming of the great plains during the era of western expansion. When he died in 1891 his remains were preserved for eternity. Comanche now resides in the Dyche Natural History Museum on the campus of the University of Kansas at Lawrence. He resides in a specially designed humidity-controlled glass enclosure.

|

| Comanche joined the 7th Cavalry on April 3, 1868. He had been captured somewhere on the southern plains and brought, along with other horses, to a remount station in St. Louis, Missouri. There, he was purchased by the Army for the existing rate of $90. Comanche had his initial breaking-in at the remount station and then was shipped with a group of other horses to Fort Leavenworth. There, Comanche had his introduction to the 7th Cavalry when he was chosen to be among the 41 horses that LT Tom Custer (brother of the General) selected to be loaded on a train bound for Ellis Station, where the 7th was encamped. He arrived at the encampment on May 19, 1868, a little over one month after joining the army. It was here that Comanche caught the eye of Capt Keogh, who was looking for a replacement for a horse that had been shot from under him in a skirmish with Indians. After eyeing the new "recruits" for several minutes, something must have made Comanche stand out as having the potential to be a good cavalry mount. Surely officers had first choice in selecting a horse for their use, and Keogh quickly ordered Comanche to be his mount. Keogh may have purchased Comanche from the army. Be that as it may, they were inseparable until that fateful day in June, 1876.

|

| There is some controversy as to how Comanche got his name. The most widely accepted story is that on September 13, 1868 Capt Keogh was involved in a skirmish with a band of Comanche Indians. During the fight the horse was wounded by an arrow in the right hind quarter. The arrow was later removed, and the wound healed. After the battle, a trooper who witnessed the incident claimed that when the arrow struck, the horse "yelled just like a Comanche" If this were true, then Comanche would have been in Keogh's possession for over four months without having been assigned a name. This seems to be an unlikely scenario, as just with a newborn infant, a name or method of identifying the child is quickly established. Another story might explain the naming delay. So it goes, Keogh was on a scouting mission near Fort Larned, Kansas. During a skirmish with the Comanches, Keogh's horse was killed. Supposedly his Lt. dismounted one of the enlisted men and turned the mount over to Keogh, who kept the horse from that point on. The horse was then named Comanche, and became Keogh's favorite mount from that point on. It is stated that at that time, with the exception of the officers' horses, it was not customary to give names to cavalry horses. |

| What did Comanche look like? As one inspects the old photos of Comanche, he appears to be dark in color, typical of the bay mounts used by the cavalry. This aberration of his true color, variously described as "claybank," "light bay" or "buckskin dun" is probably a function of the level of sophistication of frontier photography. On July 25, 1887, 2LT James D. Thomas, Acting Adjutant of 7th Cavalry at Ft. Meade, Dakota Territory, certified a description of Comanche prior to transferring his care to CPT Henry J. Nowlan, 7th Cavalry:

Name: Comanche

|

| Comanche and Keogh served with "I" Company and Keogh for the remainder of his active career. However, due to deployments of "I" Company away from the main regiment and leaves of absence taken by Keogh, Comanche missed the major battles engaged in by the unit. At the time of the summer, 1867 campaign that included the Kidder Massacre, Keogh was commanding officer at Fort Wallace. During the Washita campaign, Keogh was on GEN Sully's staff, assigned to Fort Harker. At the time of the 1873 Yellowstone Expedition, Keogh was serving on detached duty with the International Boundary Commission at Fort Totten, Minnesota, near Canada. Keogh was on leave, visiting his home land, and therefore was not a part of the 1874 Black Hills expedition. The latter proved to be more of a pleasure trip, since no significant engagement with Indians was made. |

|

It took almost a year for Comanche to recover from his wounds. His care was always under the watchful eye of Gustave Korn, the farrier, assigned to him by CPT Nowlan. Comanche quickly became the mascot of the 7th at Ft. Lincoln, and legend has it that the daughter of the commander (COL Sturgis), convinced CPT Nowlan to let her ride Comanche about the post. Then one day the daughter of another officer requested and was granted permission to ride Comanche, and when Sturgis's daughter became aware of this she became so enraged that her special status had been breached that she caused a lot of trouble around the Sturgis household. This, more than anything else probably led to COL Sturgis issuing G.O.[General Orders] No. 7: Headquarters Seventh United States Cavalry, Fort A. Lincoln, D. T., April 10th, 1878. General Orders No. 7. (1.) The horse known as 'Comanche,' being the only living representative of the bloody tragedy of the Little Big Horn, June 25th, 1876, his kind treatment and comfort shall be a matter of special pride and solicitude on the part of every member of the Seventh Cavalry to the end that his life be preserved to the utmost limit. Wounded and scarred as he is, his very existence speaks in terms more eloquent than words, of the desperate struggle against overwhelming numbers of the hopeless conflict and the heroic manner in which all went down on that fatal day. (2.) The commanding officer of Company I will see that a special and comfortable stable is fitted up for him, and he will not be ridden by any person whatsoever, under any circumstances, nor will he be put to any kind of work. (3.) Hereafter, upon all occasions of ceremony of mounted regimental formation, 'Comanche,' saddled, bridled, and draped in mourning, and led by a mounted trooper of Company I, will be paraded with the regiment. By command of Col. Sturgis, E. A. Garlington, First Lieutenant and Adjutant, Seventh Cavalry. The ceremonial order inspired a reporter for the Bismarck Tribune to go to Fort Abraham Lincoln to interview Comanche. He "asked the usual questions which his subject acknowledged with a toss of his head, a stamp of his foot and a flourish of his beautiful tail." His official keeper, the farrier John Rivers of Company I, Keogh's old troop, saved "Comanche's reputation" by answering more fully. Here is the gist of what the reporter learned (Bismarck Tribune, May 10, 1878):

|

|

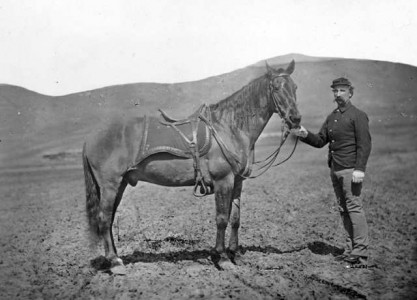

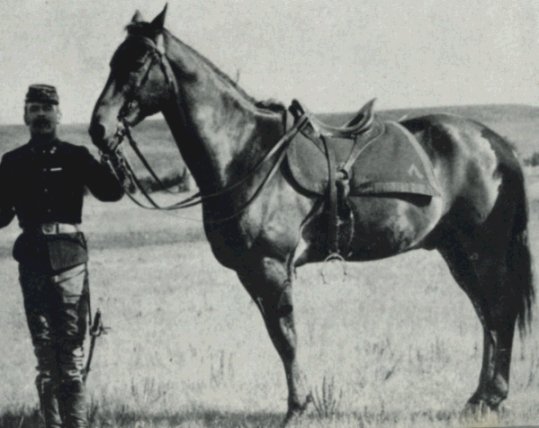

Comanche at Fort Riley, Kansas

|

| From that point on, Comanche led a free and peaceful life. he was allowed the freedom of the Post, the only living thing that wandered at will over the parade grounds at the fort without a reprimand from a commanding officer. When the bugle sounded "formation," Comanche would trot out to his place in front of the line of Troop I. He would be given sugar cubes on demand at the door of the officers' quarters and then saunter on down to the enlisted men's canteen where a specially placed bucket of beer awaited him. Gustave Korn and Comanche became inseparable. Comanche would follow Korn everywhere. When the unit returned to Ft. Riley, Kansas, it is stated that Korn was visiting a lady friend in the nearby town of Junction City. When Korn did not return to the base to feed and groom Comanche for the evening, that the horse looked all over the base for Korn, finally going directly to the house of the girlfriend to escort Korn back to the Post. When Korn was killed at Wounded Knee in 1890, Comanche's health began to slowly deteriorate. He died on November 7, 1891.

|

|

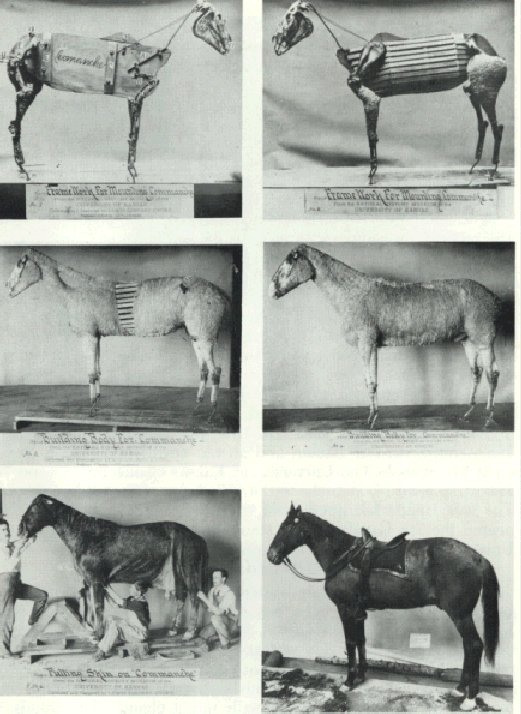

Comanche preserved forever at the University of Kansas

|

|

The officers and men of the 7th Cavalry were heartbroken. One of them suggested that Comanche be preserved forever by being mounted and kept with the unit. A famous professor at the University of Kansas Museum of Natural History was summoned to the Fort. He agreed to preserve Comanche for $400 and the right to display the horse at the upcoming Exposition in Chicago in 1893. Later, when for reasons still not clear, the bill was not paid and Dyche agreed to keep Comanche in lieu of payment. Comanche still stands there today for all to see - the "sole survivor of Custer's command at the Little Bighorn. In 2005, museum staff carefully dismantled the old Comanche exhibit on the fifth floor of the museum and restored the mount. Visitors can visit the exhibit on the fourth floor of the museum. Moving Comanche Before and after restoration Restored Comanche exhibit |

Footnote: "Comanche was reputed to be the only survivor of the Little Bighorn, but quite a few Seventh Cavalry mounts survived, probably more than one hundred, and there was even a yellow bulldog." Evan S Connell

Sources: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Comanche_%28horse%29 http://naturalhistory.ku.edu/explore-topic/comanche-preservation/comanche-preservation http://garryowen.com/

I loved reading about Comanche!!! Thanks for sharing!

Posted by: Stephanie | 04/02/2012 at 12:25 AM

Probably the only horse that has been honored by a song? A real gentle warhorse; a moving story.

Posted by: vock, Christopher | 08/19/2012 at 02:38 PM